Sad, but true: Most of us don’t like our own bodies.

Among women, body dissatisfaction is epidemic. One study found that the percentage of American women who aren’t satisfied with their bodies could be as high as 91 percent. A growing number of studies show that it’s an issue for men too. One study put the rate of body dissatisfaction in men at six in ten. Kids aren’t immune either. Multiple researchers have found that some kids begin wishing for a different body as early as age six.

Of course, there’s nothing wrong with wanting our bodies to be different than they are. Slimming down or getting fit, say, could be good goals for health reasons. But often our dissatisfaction is about our looks, not our health. And unfortunately, that preoccupation with appearance can have substantial consequences.

“Unhappiness with our own bodies takes a massive toll on our mood, our cognitive ability, our sense of self-worth, our overall energy, and our existential well-being,” says Hillary McBride, a registered clinical counselor and author of Mothers, Daughters, and Body Image: Learning to Love Ourselves as We Are. Not surprisingly, body dissatisfaction is highly correlated with a range of other conditions, including depression, anxiety, and eating disorders. And even if we don’t suffer obvious mental health effects, our worries about our bodies rob us of energy that we could invest elsewhere.

“We are preoccupied with things that we can’t—and shouldn’t necessarily—change. If we spent our energies elsewhere, what could we be doing instead?” asks McBride.

Media sources are the most well-known contributor to body dissatisfaction. “Everything—TV, magazines, the internet—tells us that our bodies should look a certain way,” says Melissa Preston, a licensed counselor and eating disorder specialist in private practice in Denver, Colorado. “We’re taught from the moment we’re born not to like something about ourselves.”

While there’s relatively good awareness these days of how media sources shape body image, several other sources contribute as well. For one, there’s peer influence. We are hardwired to crave a sense of belonging, says McBride, so how our peers view us—and, specifically, how they view our bodies—has a big impact.

Even more important than peers, though, is parents. “Mothers in particular are the number one most influential figures in how kids feel about themselves,” says McBride. And it’s not just what mothers say to kids about the child’s body that’s important. “What mothers say about their own bodies is the best predictor of how kids will feel about their bodies,” she says. “Think about all the times girls see their mothers stand in front of the mirror, pull at their skin, and make a disparaging comment.” Kids learn from these kinds of comments what bodies are “supposed” to look like, McBride explains, and they then evaluate themselves negatively when they don’t match up.

An Action Plan for the Whole Family

Worrying about our looks may not be productive, but it’s hard to stand in front of the mirror and celebrate wrinkles and cellulite. How, exactly, are we supposed to come to terms with our own bodies—and help our kids and spouses come to terms with theirs?

Start With Yourself

In order to cultivate a healthy body image in your children and partner, the place to begin is with yourself. That’s because how we view our own bodies has a substantial impact on how our kids, spouses, and peers view their bodies. So start with these key steps to develop a healthier view of your own self:

Give attention to what your body does for you, not just how it looks.

Instead of noticing only your appearance, take some regular time-outs to ponder and celebrate all the things you experience through your body, such as walking, running, tasting flavors, hugging people you love, climbing mountains, giving birth, or savoring the smell of baking bread. “Don’t just look at yourself from the outside, but feel what it’s like to be alive,” says McBride.

Name out loud some small aspect of your body or your appearance that you like.

The tendency, says Preston, is to notice only negative things about ourselves and miss the positive. But it’s a healthy practice to look in the mirror and celebrate little aspects of yourself that you like—your smile, for example, or your hair. Then, verbalize these positive aspects of yourself. “Out loud is so much more reinforcing,” says Preston.

Change your media use.

Since media images are so significant in prompting body dissatisfaction, managing exposure is crucial to promote a healthier self-image. For starters, says McBride, choose not to watch shows, follow social media accounts, or read magazines that make you feel worse about yourself. And for the media that you do view, train yourself to think critically about it. When you see a magazine photo, for example, be realistic and acknowledge that’s not what a real woman looks like—that’s Photoshopped. Be on the alert to explicitly identify how and why people’s bodies are being used in media imagery and what messages are being promoted by that imagery.

Counteract the influence of your own parents.

If your parents communicated a negative view of your body—or of theirs—search out new influences to spur you toward a healthier view. “Find people you trust to build you up,” says McBride. These don’t always have to be people you know, she says. Even reading books that offer a healthy view of the human body can help.

Say no to “fat talk.”

Women often bring themselves down in order to bond with other women and to make their peers feel better about themselves, says McBride. But talking negatively about our own bodies—and, in particular, talking about our own “fat”—is harmful to both ourselves and our friends. “Refuse to have those conversations,” says McBride. “Say, ‘I love talking to you, but I don’t want you to talk about yourself that way. Instead of talking about what’s wrong with our bodies, let’s appreciate them and all we can do and experience because of them.’”

Nurture Your Children

Once you’ve dealt with your insecurities about your own body, you’re already well on your way to fostering a healthy body image in your kids. But to spur their development further, try these tactics:

Once you’ve dealt with your insecurities about your own body, you’re already well on your way to fostering a healthy body image in your kids. But to spur their development further, try these tactics:

Minimize compliments on your

child’s appearance.

This advice is counterintuitive, says Preston, since parents assume that telling children they look good will help kids feel positive about themselves. But even positive comments about appearance still send the message that looks are important.

With girls in particular, talk about what their body is able to do.

It’s normal to talk to boys about how their bodies perform and what they are able to accomplish with their bodies. (For instance, “You’re so strong.” “You did a great job at the ball game!”) But with girls, even the most well-meaning adults tend to focus on how the girls look. (For instance, “You look so cute today!” Or, “That dress is darling!”) According to Preston, the focus for both genders should be on what we can accomplish and experience through our bodies.

Promote media literacy in your kids.

Watch media with your child, and ask targeted questions about what they’re viewing. For example, “It’s interesting that all the main characters are incredibly muscular. Do you know anyone who actually looks like that?” Make sure to have these conversations with both girls and boys, says McBride.

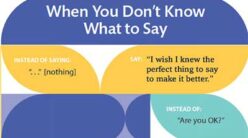

When your child expresses concerns about their body, respond with empathy.

“It’s OK if your child has a bad body-image day. Don’t just shut it down,” says McBride. Instead of dismissing their concerns, you can acknowledge that it’s hard and that you, too, are bombarded with messages that you’re not good enough. Then you can redirect your child’s focus: “Your body walked you over here to me. Your body is beautiful and powerful.”

Nurture the Man in Your Life

According to Tiffany Brown, Ph.D., a research fellow at the University of California, San Diego’s Eating Disorders Center for Treatment and Research, media presentations of men have changed significantly in recent years, and now men, like women, are increasingly feeling pressure to achieve an idealized form.

Think of the Batman movies, for example. The main character in the newer movies has become far more lean and muscular than in previous movies, in a way that is just as unrealistic for men as the Barbie figure is for women. (This change reflects the fact that the ideal for men is different than for women. Whereas women typically want to have low body fat, men want low body fat and significant muscularity. In other words, says Brown, “Men can have concerns that they’re both too big and too small.”)

For better or worse, a wife can impact how much pressure her husband feels about his body. “When spouses pressure their partner (overtly or subtly) to look a certain way, that definitely is associated with a large increase in body dissatisfaction,” says Brown. “Conversely, when people get into healthy relationships that focus on all the other qualities that the partner appreciates about them, they start to feel more satisfied.”

To help your spouse combat the pressure, use strategies similar to those you use for your children. For starters, redirect the focus away from what your spouse’s body looks like. Obviously, steer clear of negative comments (“You’d be more attractive if you lost weight”), but be judicious even about compliments, since they reinforce the message that appearance is what matters. “We need to be aware or mindful of what we’re reinforcing and make sure appearance is not the only thing we’re complimenting on,” says Brown.

Additionally, communicate a message of unconditional acceptance. People often think that if they encourage their spouse to work out or avoid unhealthy foods, it will promote healthy behaviors, says Brown, but that tends to backfire. The reality, she says, is that acceptance of your spouse—just as he is—is more likely to encourage healthful habits.

Jamie Santa Cruz writes from Colorado, one of the healthiest states in America.