Some skeptically eye sheer ice and hard-packed snow as hazardous places to slip or crash out of control. But if you tried pegging hope’s fullest potential in degrees Fahrenheit, it would be on H2O at 32 or less–at least for winter athletes racing for Olympic gold. At these temperatures, water that once felt soft as a kitten’s paw or frothy like bubble bath suds hardens into something cold and carvable by skate blades and ski edges.

Speed skater Derek Parra and alpine skier Caroline Lalive compete on these frozen platforms of ice and snow at top speeds–up to 35 and 85 miles per hour, respectively. Why? It gives them a ticket to fly. All their training since childhood focuses on going faster. So, despite the potential danger and disappointment high-level participation presents, these two Americans plan on setting personal best records at the 2002 Winter Olympic Games in Salt Lake City, Utah.

The classic victory image of flags, flowers, and flashbulbs represents the end game, and it remains fixed. However, the means to this end couldn’t be more customized. Besides designer workouts, Parra and Lalive each bring faith experiences as unique as a snowflake to cope with the vice- griplike pressure.

For instance, with talent and training being more or less equal at their caliber, even the secular athlete knows it takes faith, if only in one’s self, to produce that coveted performance X factor–confidence. But as Christian athletes, these two agree that their confidence comes from Something beyond themselves. In the midst of thrills and spills, faith in Christ helps them succeed in and out of their Spandex skin-tight uniforms. Here are some snapshots of two racers soon to blur across your TV screen:

DEREK PARRA

Have you ever seen those tracks where the car is on a rail? It feels like you’re on a rail, and you’re getting whipped around the turn. When it’s a good day on the ice, it’s like leaning your left shoulder into the car window and just hanging there with the centrifugal force. It’s like riding a bike in the perfect gear. It’s almost like you’re floating. It’s like, “Yes! I am going so fast!”

Long before he hungered for gold, Derek Parra jokes that he thirsted for sodas. They cost nothing at San Bernardino’s Stardust Roller Rink–if you finished the two-lap fun event faster than the other kids. So when he debuted there at age 14 without much jingling in his pocket, he quickly picked up the pace until he had a fistful of maroon tickets to cash in for carbonated drinks.

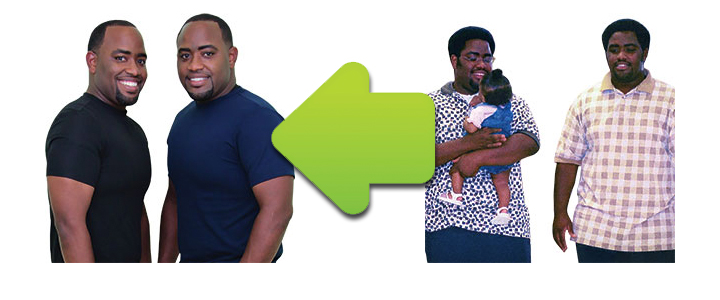

When the in-line skating craze exploded in the U.S., Derek sped into a whole new world as a Team Rollerblade exhibitor. Upon retiring in 1996 he had earned 18 individual gold medals and stood as the most decorated athlete at the 1995 Pan-American Games. But to skate toward his Olympic dream, he had to trade in his wheels for blades, since in-lining is not yet a category.

Rock Bottom

In 1997, only a year into this transition, Derek dejectedly glided off the outdoor oval in Balsega de Pine, Italy, after barely finishing his first speedskating 10K world cup competition. He blamed the tears in his bloodshot eyes on the drizzle that pockmarked the ice into a sandpaper surface–until a Dutch skater rushed up after the race.

“Are you still alive?” she inquired of his physical meltdown. The gun cracked, and he had sprinted too fast too soon. Furthermore, he sat back on his blades to ride the bumpy surface, but the tactic only tightened his leg muscles like guitar strings. His competitors soon nearly lapped him. Then, like the wet weather, bone-weary fatigue found every cranny of his frame. His Olympic dream seemed drowned in an ice-cold puddle.

“I came from being number one in the world [as an in-line skater] to being beaten at first by girls that were 12 years old. On that day I was so tired, but I went on this jog in the snow afterward and cried to God, `Help me, help me. Give me a clue.'”

After all, he paid some dues to get that far. To buy equipment and get to training camps, Derek had mowed lawns and delivered the Penny Saver shopper paper. He occasionally sold all his nonessentials–from his camera to his Guess jean jacket. He hitchhiked. In this way, he once got from Colorado Springs to Couderay, Wisconsin. There he beseeched training ground owners Brad and Jeanette Bradner to let him work in their small skate factory and in grounds maintenance in exchange for the program.

Turning Points

Derek stayed on at the Bradner place to train and lived in a ramshackle mobile home surrounded by thick Wisconsin woods and an occasional black bear. Going without plumbing or electricity in his remote sleeping quarters forced him to think more about his dreams, his fears, and his faith. That’s when the Bradners’ son Bruce handed him a Bible and encouraged him to “read it and see if it helps you.” Derek opened it nightly by candlelight.

“When my parents divorced they got away from taking us to church. I got away from religion, but I never lost the belief. That’s when I came back,” Derek recalls. Today he’s duct-taped that Bible’s spine twice.

Like other skaters, Derek trains on and off the ice with resistance, distance, and sprints twice a day most days. However, after viewing a videotape of five-time gold medalist speedskater Eric Heiden’s 19-jump workout, Derek developed an expanded 32-jump workout. He begins this four-hour exercise by strapping on a vest packed with 40 pounds of sand, lead, and BBs.

With the Olympics in sight, Derek admits he could put blinders on to skate without distraction. But for him, that kind of focus backfires, because it warps reality too much. Skating can easily become the whole pie of life versus a slice of it. So he’s doubly thankful for his faith, his wife, and even his part-time job at the local Home Depot’s Electronics Department.

“Jesus, guide my feet and keep me safe,” Derek recites. “Then, it’s like Charlton Heston’s words when he plays Ben-Hur. I say, `Lord, I give You my life. Do with me what You will.'”

CAROLINE LALIVE

Skiing is pretty sensory-oriented. It’s a lot of touch and feel. Slalom, which is really quick, is like a dance. You just get in the rhythm and keep that flowing movement going. Downhill is similar to riding a roller-coaster . . . and like squatting to a 90-degree angle against a wall for two minutes. But as soon as I take off, I don’t hear my skis or the wind blowing through my helmet. It’s a serene place-a combination of being relaxed and at the same time really focused. Because I’ve skied since I’ve walked, for me it’s like walking. But you’re at the mercy of the elements.

Caroline Lalive’s Olympic dream started when, at age 8, she watched Swiss skier Pirmin Zurbriggen win gold in the downhill event at the 1988 Calgary Olympics. After he gave his acceptance speeches in a thick French accent, Caroline trounced into her bedroom and, though her father is Swiss and she speaks French fluently, began giving interviews in a fake accent: “Ah yes, it ees so nice for me to vin zees mettal . . .”

Behind the Scenes

After six years with the U.S. Ski Team, Lalive has a good shot at giving this speech accent-free. But she shares that achieving an Olympic opportunity for the second time in her short life comes at the cost of the comforting familiar things of life. She missed “hanging out” with friends, attending school social events, rooting for the football team.

“Don’t get me wrong,” Caroline quickly qualifies. “It’s a very privileged opportunity I have. But it can be very draining in all areas of your life. It’s not what you would call a normal lifestyle. You live out of a bag. You’re lucky if you can do laundry. You eat mystery meals for months on end. When you’re sick on the road, you’re not allowed to take any medicines due to antidoping.”

Plus, how many people spend 24/7 time with their coworkers–ultracompetitive ones after the same promotion? That’s why she stresses keeping “ties to the real world” by maintaining a healthy relationship with God, family, and friends. She also periodically revisits the reason she’s on skis.

“The emotion I have and the passion is my display of how much the Lord means to me and how much the sport means to me,” she reflects. “To bring those two together is so exciting!”

Crash Course

Sometimes circumstances still dampen that joy. In February 2001, at the World Championships in St. Antonam Arlberg, Austria, Caroline was poised to move from second place to first place–to being recognized as the world’s best women’s skier. Thirty thousand people and her mother, filmed live by NBC, watched from the finish line far below. She heard them cheering, lost her focus, and fell, which injured her knee and hushed the crowd.

“Lord, how hard would it have been to just let me win?” she remembers praying. She started wondering why she

habitually seemed to get so close to the top spot only to miss it. “I kept seeing other people not called to Christian standards having fantastic races, and I was just clinging to the Lord and feeling really defeated. I knew I was gifted, but I just couldn’t get over the hump.” She nearly retired.

But before crashing in the snow and “cashing in” her spirit, Caroline confesses that she spent time in prayer and Bible study to somehow earn God’s blessings of protection and success. With time she began seeing how she put God in a box, that His blessings may be bestowed in areas she had not yet begun to appreciate.

“I am in a very secular arena, and I really grab hold of that truth in Philippians 1:6 to be confident that God has placed me in this arena for a purpose, a good work. I want Christ to use me, even if it’s just to encourage someone without necessarily saying, `You need the Lord.'”

Warmups

To ski like a streak down the mountain, Caroline often reads books or listens to opera. But she says that the half hour before competing turns from calm to “epic” in intensity. While her coach methodically punches her arms and legs, he launches into their habitual banter on the snow:

Coach: What are you going to do?

Caroline: Deliver the message.

Coach: What’s the message?

Caroline: Victory in Jesus!

Coach: I want an “express” delivery.

“Before I race, I quote Scripture to one of my coaches, though he’s not a Christian. I pick something from Psalms or Proverbs, and I write it on a little strip of paper and stick it in my pocket. While I’m riding up the chair lift in the morning, I’ll pull it out and try memorizing it. Then I share it with him.

“I’m huge on prayer before my race, so I’m also just beseeching the Lord, `Just give me Your protection.’ This coach stays with me. Lots of people would put up a wall. But he is so willing and genuinely interested. And when I do have a great race, and the Lord has truly blessed me, he says, `Make sure you thank Him, Caroline.'”